Overview: Dr. Manhattan’s actions that led to the changes in the universe are revealed, as he takes a moment to remember all of his memories from the first time he arrived in DC’s multiverse.

Overview: Dr. Manhattan’s actions that led to the changes in the universe are revealed, as he takes a moment to remember all of his memories from the first time he arrived in DC’s multiverse.

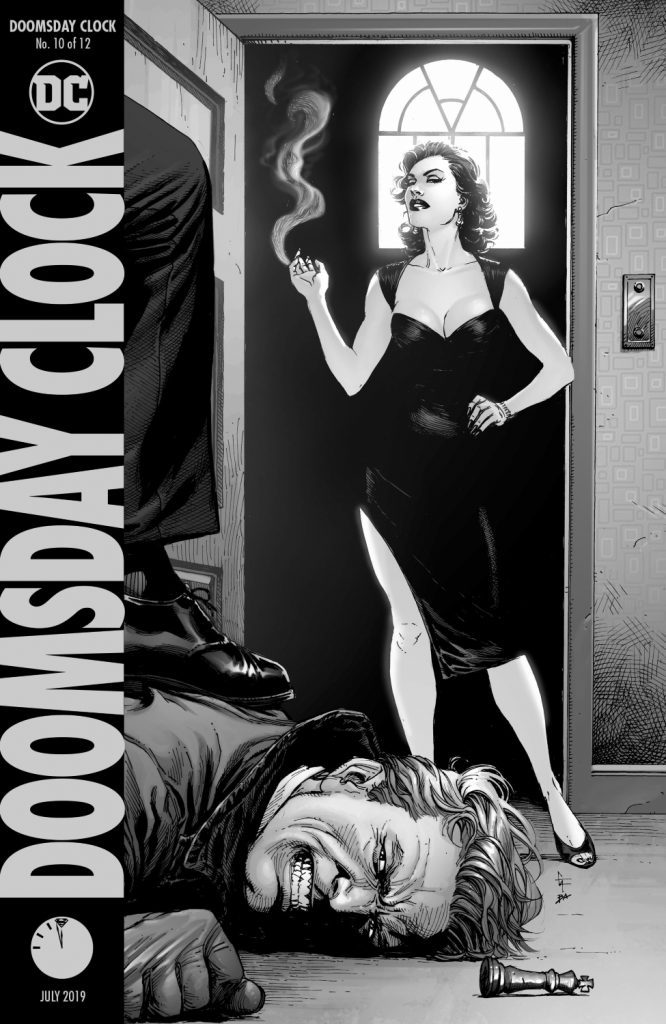

Synopsis (spoilers ahead): The issue opens with a Nathaniel Dusk scene, the black and white movie that serves the purpose that the Black Freighter did in the original Watchmen. In the scene, Nathaniel is on the ground. Murray, his cop friend who enlisted his help to solve the case of the murder of two men who were playing chess, holds him down under his foot. Then, comes into the scene a typical femme fatale type: black dress with a deep neckline with high heels. She is Joyce Gulino, the woman Nathaniel believed to be dead, the supposed love of his life. An unexpected player, Joyce reveals to be the one behind the killing, even though she never pulled the trigger.

They’re heading to a big moment, except… Carver Colman, the actor behind Dusk, forgets his line. We’re now in full color. He’s already forgotten his line thirteen times. He’s a bit out of it, having received a letter threatening to expose his “darkest secret”. The scene that follows has Joyce giving him a glass globe of the world, a present that is meant to make him remember her and how he loved her. He uses the globe as a weapon against Murray. As the globe shatters, Dr. Manhattan’s caption reads “Worlds live, worlds die. Nothing lasts forever.”

We’re now on Mars, as all of the superhero groups who have come to face Manhattan crumble to the floor, suffocating in the no-oxygen atmosphere. Manhattan is now remembering his last encounter with Ozymandias, just before he vanished in the original Watchmen series. He said that that he would leave the galaxy for one less complicated. And so he entered the multiverse.

Drawn to Superman’s world in the golden age, the first person Manhattan speaks to is Carver Colman. After much duress in his life, Colman had ended up on the streets. On his first night sleeping under the moon, a police officer comes to tell him to leave the alley, for “this is Hollywood Boulevard.” At this point, Manhattan arrives. He takes Colman to a diner and there they share a meal – eaten only by Colman – and some conversation. And then on and on, Colman and Jon – as Manhattan introduces himself – meet again in the same diner, Colman’s life ever improving. He gets an acting career, he gets an Oscar, and then Jon reveals to him one day that he doesn’t see Colman in the world in one year.

In the meantime, on April 18, 1938, Superman is spotted for the first time. In this timeline, the original Golden Age Justice Society is formed. Except Superman would be seen again for the first time multiple times. Manhattan realizes this is the center of the Multiverse, the Metaverse, and an outside force keeps pushing the arrival of Superman to Earth forward in time, an event that sends ripple effects through all of the multiverse. He tries his hand at changing reality, removing the original Green Lantern from the reach of Alan Scott on the day he’d first get in touch with it and thus eliminating the chances of the Justice Society ever existing. From his interference surfaces the New 52 universe.

Except, the universe, by means of Wally West, fights back. In the future, he sees Superman coming after him, and everything turns black. Either Superman has destroyed him or he himself has destroyed the Metaverse.

Analysis: Like a butterfly effect, Manhattan’s single, simple action that sent changes rippling through the universe and led to the New 52 is revealed. Stretching out towards the past, he avoids Alan Scott from ever becoming the Green Lantern. We all know that, in fact, the New 52 has nothing to do with Manhattan or any such in-canon happening and everything to do with a reshaping led by the publisher. And yet, it works.

In some incredibly nonsensical and ridiculous way, Geoff Johns and Gary Frank managed to weave a convincing argument for why there was a bit less hope, a bit less cheerfulness in the New 52 world. It is a bit more Watchmen, Manhattan’s own world, a bit less innocent – an innocence represented by the Justice Society of America. Erasing the JSA, erasing the Golden Age, that inherent core that makes DC’s characters be lighthearted was gone. And yet, it feels slightly forced.

There was no way mixing Watchmen with the regular DC universe wouldn’t lead to mixed feelings and some incongruences, and the solution presented is both brilliantly simple and spectacularly non-comprising to the original material. Suddenly, instead of having a timeless conscience that walks through time as if it were a physical dimension, Manhattan also has the ability to move his own body in the past, changing his own timeline. This is more than omniscience in relation to quantum physics and relativity, this is time-travel, a concept unexplored by Moore and Gibbons in their original oeuvre.

But then again, it fits the character in a peculiar way. Manhattan – or, better yet, Jonathan Osterman – has a curious brain. He was a watchmaker and a scientist, he experiments and sees things working and arrives at conclusions. Suddenly, after becoming the Naked Blue Guy, he now sees everything. He’s bored. He needs something new to discover. Like a child with an ant house, he tries puncturing a hole in the bottom to see what happens. A lot of dirt leaks from the hole, disrupting some of the tunnel connections. While most ants reconstruct the tunnels and continue with their lives, two of them escape and bite his hand. Wally West and Clark Kent were their names.

As anyone would see, Doomsday Clock is born and raised as a comic that would never be read or appreciated at its own merits, which leads to the constant feeling of not knowing if this is a spectacular comic or a half-brother who slightly resembles its older sibling and yet is not quite the same. The structure of the side narrative – The Black Freighter in Watchmen, Nathaniel Dusk in Doomsday Clock – puts it as a half-brother who is trying too hard to be like his oldest. The narrative itself and especially, very much stellarly especially, Gary Frank’s art and Brad Anderson’s coloring alone would take it to the higher levels of comicdom. Under Anderson’s colors, Manhattan shines. His eyes shine even brighter, the flat colors take an entirely new depth. Under Frank’s hands, the hay comes back and forth with the wind produced by Kal-El’s spaceship hitting the ground.

So, torn between the marvelous and the unfulfilled, one might find himself either loving, hating, or having a high appreciation for the exceptional inner workings of a, particularly unexceptional clock. This last one is me.

Final Thoughts: While the quality of Doomsday Clock never fails to reach high levels, the premise and the conduction are beginning to stretch themselves a little thin.