Editor’s Note: This new article series started with an assignment of a review regarding the book Batman and the Joker: Contested Sexuality in Popular Culture by writer Chris Richardson. After much consideration and thought, the review morphed into something much larger. The sexuality of Batman has been contested for years and this series looks at the finer elements of each side of the argument. Given the content discussed, reader discretion is advised.

In June of this year, an interview between Variety and Harley Quinn: The Animated Series co-creator Justin Halpern went viral after Halpern revealed that a joke in the adult animated series depicting Batman giving oral sex to Catwoman was nixed by DC. “Heroes don’t do that.” Halpern recited, “It’s hard to sell a toy if Batman is going down on someone.” Online fandom was abuzz with bemusement, with memes, video essays, and articles articulating incredulity at the idea that cunnilingus would be the bridge too far for a character so consistently enjoyed by adults.

This is only the latest disagreement of what constitutes proper mature storytelling regarding Batman. For decades, superhero fans have been split in viewing the character between the colorful lens of the 60s TV series and the gothic grit of the eighties Dark Knight miniseries. The dissent has only worsened in recent years. After the appearance of The Caped Crusader’s penis in Batman: Damned #1, an ill-conceived sex scene that resulted in the universal rejection of the animated Batman: The Killing Joke adaptation, and the polarizing portrayal by Ben Affleck in 2016’s Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice, the conspicuous suggestion is that Batman lends himself to stories directly involving sex and violence and precludes children.

The edited lower body silhouette of Bruce Wayne’s anatomy

Batman hasn’t been the only character subjected to this debate. When 2013’s Man of Steel reopened the schism in superhero fandom, subsequent Superman media (and online discourse) responded in varying ways to the serious approach that the film proffered, either relishing or rejecting its realism. The examples continue with Marvel. The influx of comic adaptations in the rival company’s Cinematic Universe has resulted in various changes to the source material, often for the sake of plausibility and suspension of disbelief. In addition to technology, and character dynamics, alterations to character motivations or characters entirely are done to keep the films reasonably mature, albeit still suitable for kids. Yet this, too, is a microcosm of something larger.

Part of comic books’ ongoing struggle with relevance has been its place in pop culture, bouncing between fits and starts of definitive adult works like Maus and the works of Will Eisner with fond memories of the Super Friends. With comic books like Watchmen and folktales of old Marvel Comics, experiments in mature themes are how superheroes continue to surprise an unfamiliar mainstream audience, measuring surprise when a genre sheds its former reputation as kiddie fare without discarding it entirely. Batman media has redefined the perception of superheroes repeatedly, with the 1989 Tim Burton film, Batman: The Animated Series, and the Dark Knight films by Christopher Nolan enjoying looming cultural status as the pinnacle of the genre. So – then – it would seem as though the concern of public acceptance for superhero media in any tonal range has long been settled by this and other franchises. Any anxiety over how others might see Batman, as campy or serious, should be alleviated.

But the anxiety remains, as evidenced by Justin Halpern’s interview. So, what’s really going on here?

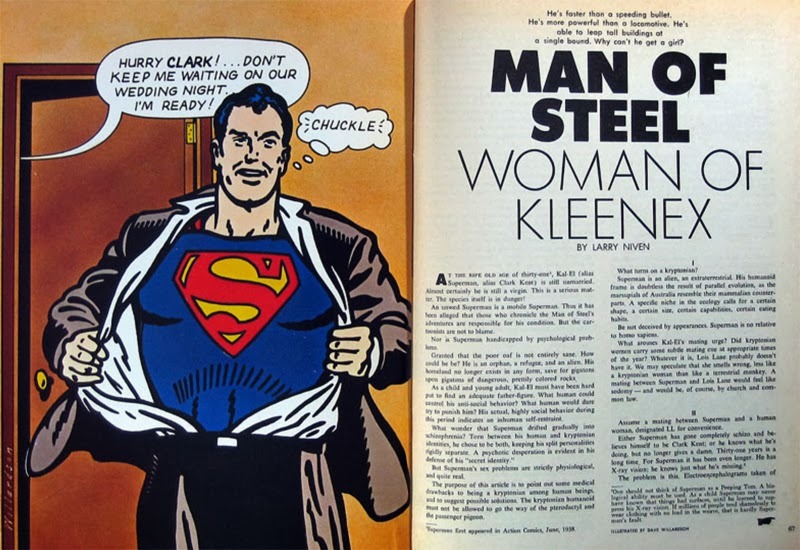

The issue isn’t how others will see Batman, but how they – both fans and DC Entertainment – see themselves through him. The quote by DC was a surprising line in the sand, as the company has generally stayed out of the way of major deviations to the character. Compounding the theme of conflict in portraying superheroes is sex, which – next to fascism – simultaneously exists as a provocative subject in superhero storytelling and the most discoursed topic in writing circles, both fan and professional. Since the days of the Tijuana Bibles from the early twentieth century, conceptions of the erotic, social and political implications of superhero sex have attracted interest in hypothesizing the genre’s limits. (One of the more popular critical texts on the subject is science-fiction author Larry Niven’s “Man of Steel, Woman of Kleenex” which posits the deadly realities of a believable sex life between Superman and any of his lesser-powered love interests.)

This essay will determine what the conversation of Batman’s sexuality speaks of both the fans and producers of his franchise. It will examine the various flashpoints of its development, from the publication of Seduction of the Innocent in the 1950s, the 1966 television series, and evolving sexuality throughout the 1970s, 80s, and 2000s. Through fusing the mediums (comics, television, and films), fan reaction will be analyzed, returning to the events of this year and understanding how the influence of culture capriciously expands both Batman’s storytelling latitude, and how engagement with the franchise advances fan’s social understanding more progressively than the manufacturers themselves. For this essay, both by way of originally mandated assignment and more psychologically relevant when discussing Batman, Batman and the Joker: Contested Sexuality in Pop Culture by Chris Richardson will be the overarching text that will be referred to, regarding analysis on our key examination. Its summation of character, stating that “Batman’s many disparate representations in serialized media reveals endless possibilities of gender and sexuality, questioning while attempting to impose stringent and coherent categories and practices.” (Richardson, 2020) will round us center to achieving a stronger cultural understanding.