Editor’s Note: This new article series started with an assignment of a review regarding the book Batman and the Joker: Contested Sexuality in Popular Culture by writer Chris Richardson. After much consideration and thought, the review morphed into something much larger. The sexuality of Batman has been contested for years and this series looks at the finer elements of each side of the argument. Given the content discussed, reader discretion is advised. Before diving into Part One: Batman’s “Seduction of the Innocent,” you can find the introduction of the series here.

The Contested Sexuality of Batman: Mainstream Culture vs Online Fandom

Part One: Batman’s “Seduction of the Innocent”

An infamous panel from Batman #84, art by Win Mortimer. Notice the slight separation of the twin headboards.

Trace the evolution of the comic book medium from the early twentieth-century newspaper strips to modern-day digital media, and track the history of screen adaptation, beginning with the film serials of the 1940s and arriving at award-winning adaptations such as Black Panther and Joker. Within that history, however, reveals the medium’s near-destruction from the highest political offices in the country, with gradual reappraisal from academics taking decades to emerge. While today’s criticism is that superheroes offer little more than mindless violence to America youth, in 1954, the Senate Subcommittee Hearings argued that comic books were “an important contributing factor in many cases of juvenile delinquency.” (Nyberg, 1998) The figurehead of this movement was Dr. Frederic Wertham, a psychiatrist and author of the popular anti-comic book screed Seduction of the Innocent, in which he made multiple assertions that comic books inflict harm onto their young readers. The violent imagery of EC Comics’ crime and horror books contribute to racism and misogyny. Superman represents fascism and encourages children to be bullies. Wonder Woman was a bad role model for young girls for her physical superiority to the men around her, and for presenting questionable sexuality with fellow Amazons and an all-girls sorority. Most famously was his charge against Batman. Wertham’s claim that Batman and Robin present a gay lifestyle that threatened the sexuality of its young male readers terrified DC, resulting in a response that had consequences felt to this today, on whether Batman presents either an ideal masculine identity – or an ideal queer one. (Richardson, 2020)

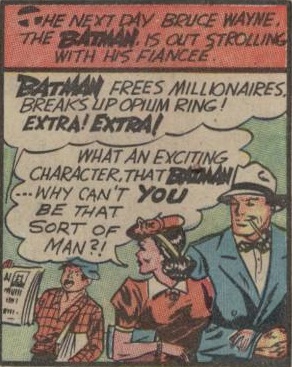

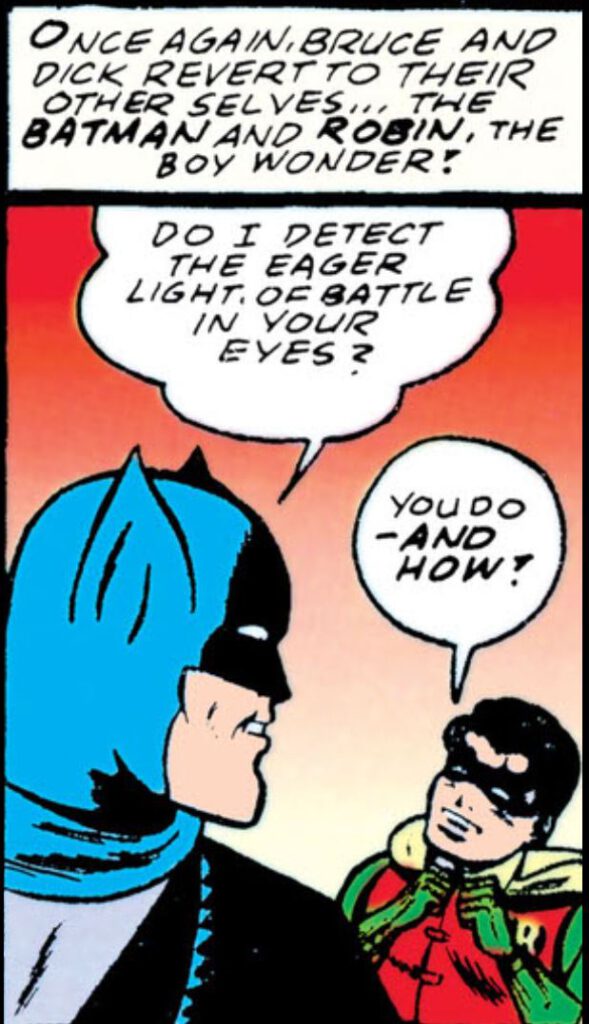

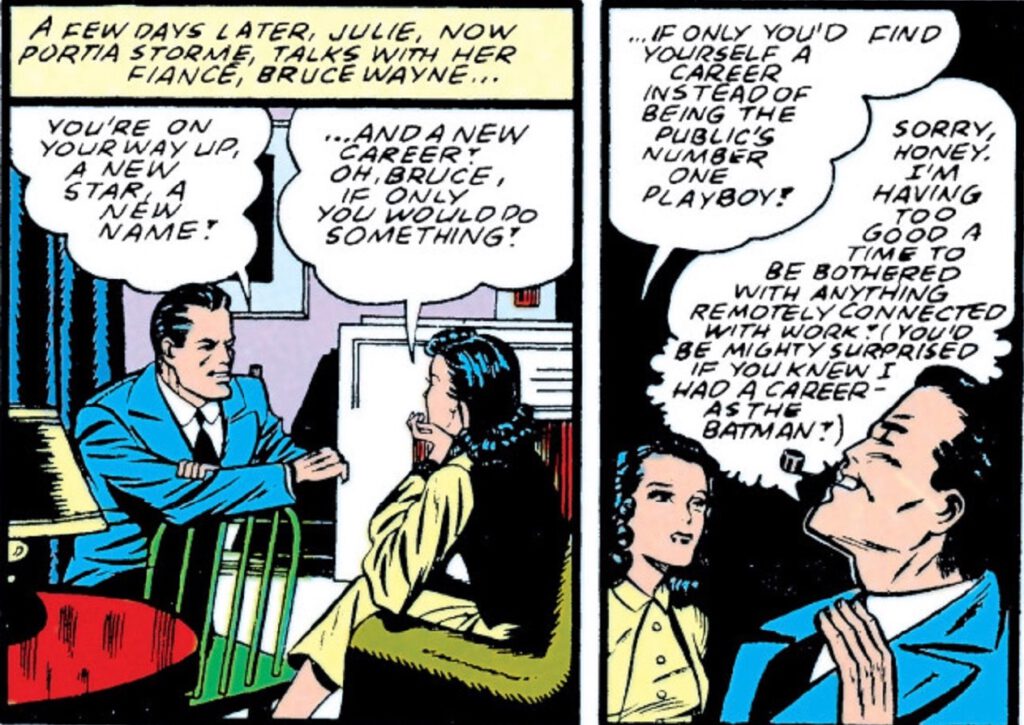

Let’s backtrack to the previous decade and examine Wertham’s reading of the Batman books by looking at the love interests most prominently featured. In Detective Comics #31, the character Julie Madison is introduced as Bruce Wayne’s fiancée in a gothic two-part tale depicting a battle between Batman and vampires. The couple’s meeting and courtship has taken place off-panel, and their romance is a presumption of fact rather than fully illustrated on the page. Subsequent appearances are scarce; she’s completely absent in the origin story of Robin, in which her fiancé adopts a circus orphan and has him live in his house. She makes a final page appearance in the next issue, where she compares Bruce unfavorably to Batman while reading of the latter’s exploits (as seen in the panel below). Detective Comics #40, a mix of both the vampire adventure and Julie’s subsequent appearance, finds her in the middle of a murderous plot bemoaning the fact that her boyfriend is a lazy good-for-nothing, unlike the “dashing” Batman. Her character’s sendoff is in Detective Comics #49, where she calls off her engagement to Bruce for never making something of his life, instead of “being the public’s number one playboy!” Bruce responds “Sorry honey! I’m having too good a time to be bothered with anything remotely connected with work!” while thinking to himself “You’d be mighty surprised if you knew I had a career as the Batman!” (This is seen in the panels at the bottom of this article.) Later in the issue, we see Bruce with Dick residing in their house and learning of the villain Clayface’s escape from prison. “Dick, get out our work clothes! We’ve got a job to do!” The following panel reveals Batman and Robin completing their costumed dress as the narration caption reads “Once again Bruce and Dick revert to their other selves…The Batman and Robin the Boy Wonder!” A smiling Batman turns to his partner and says, “Do I detect the eager light of battle in your eyes?” Robin smiles back and replies, “You do! And how!” (Also shown in an image below.) The exit of Julie never crosses his mind for the rest of the story.

from Detective Comics #39, art credited to Bob Kane

Weeks later Bruce is attached to a previous acquaintance in Linda Page, nurse and former society girl. She’s introduced in the story by bumping into him on the street, where he learns of her career change. He chides her for giving up the rich life of a society girl and committing to an honest job. Linda inherits Julie’s role as the finger-wagging female who urges Bruce to do something with his life, only for Bruce to share a laugh with readers that his double life as the Batman more than makes up for anything Linda could imagine for him. Often the two’s courtship would be sandwiched between scenes of Bruce and Dick Grayson relishing their costumed double life and discussing how his time spent with Linda might affect his hours as Batman. This gets compounded in Batman #5, where Bruce fakes a public engagement with the Catwoman to rehabilitate her of her criminality.

A ridiculous scene from Batman #5, art credited to Bob Kane

Bruce ends up breaking the hearts of both women. He enacts this plan without Linda or Dick’s knowledge, and this reveals to Catwoman that their romance was fake. The final panel summarizes the events thusly:

Bruce: “I’m glad that’s over! I hope Linda will forgive me now!”

Dick: “She will Romeo! But will the Catwoman?”

This was the mean average function of women in the pre-code Batman comics – foils for Bruce Wayne’s cover as a playboy yet never serious romances who endanger his nighttime career as the Batman. Boys would read the women in Bruce’s life like public appearances and homework – aspects of societal normalcy that get tossed aside once crime-fighting calls.

In Seduction of the Innocent, four straight pages were dedicated to Batman in the seventh chapter titled “I want to be a sex maniac!”. (Wertham, 1954) Here, Wertham claims that Batman presents not only a homosexual relationship with Robin (thereby a predatory one as Robin is his adopted ward), but one that intentionally appeals to children. The following points made up his case, with some instances reported from case studies involving real child patients (more on that later):

- “Bruce Wayne was rich. Several of Wertham’s patients said they wanted to live with Bruce and be rich too. ‘It is like a wish dream of two homosexuals living together.”

- “Alfred served lavish meals and kept Wayne Manor filled with freshly cut flowers.”

- “Batman and Robin spent a lot of time caged, trapped or tied up while the other tried to save him. ‘Like the girls in other stories, Robin is sometimes held captive …. They constantly rescue each other from violent attacks by an unending number of enemies. The feeling is conveyed that we men must stick together because there are so many villainous creatures who have to be exterminated. They lurk not only under every bed but also behind every star in the sky”

- “Bruce and Dick must be homosexual because there were no women in their home.”

- “Bruce and Dick had to be homosexual because the only women in their lives were criminals like Catwoman.”

- “Bruce Wayne wore pajamas and dressing gown around his house; he sat on the same sofa or couch as his youthful ward; Dick often sat at Bruce’s bedside when his guardian was injured or ill.”

- “Robin had no pants on.”(Wertham, 1954)

from Detective Comics #49

Putting aside that the average American who self-identifies as queer today is up to 5.6% (Gallup), much of Wertham’s claims come down to simple stereotyping. Between the “lavish meals” and “freshly cut flowers” found in Wayne Manor to Batman and Robin rescuing each other from danger – a trope endemic to adventure stories from the past century, his “research” reveals little beyond the prejudicial views he carried in arriving at the project. Nevertheless, he chose to ride the wave of moral panic, the so-called “Lavender Scare” by adding comics to the mix. It was during this time that President Eisenhower signed into law the dismissal of all federal employees who identified – or were suspected of being – homosexual, under the rationale that queer people were susceptible to blackmail and thus posed a security risk. With Executive Order 10450, “Sexual Perversion” was the term used to keep people from holding positions in government. It was also a retort employed by Senator Joe McCarthy against critics of his anti-Communist agenda. Before long, the concept of being gay in America meant one was “godless”, “morally weak” or “psychologically disturbed.” (Judith Adkins, 2016)

The accusations stuck, and the public backlash destroyed sales. Comics publishers who didn’t go out of business came together to create the Comics Code Authority–a standards guideline rigorously enforced to keep the appearance of good taste and proper content intact, with its seal of approval found on every comic book cover. Wertham’s case against Batman was legitimized by the seismic shift, even though his conclusions were shallow. This remained apparent until well before 2013 when Carol Tilley – an Assistant Professor at the University of Illinois’s Graduate School of Library and Information Science – published her findings on Wertham’s research after the Library of Congress made them available to the public. In Seducing the Innocent: Frederic Wertham and the Falsifications that Helped him Condemn Comics, Tilley details how Wertham “manipulated, overstated, compromised and fabricated evidence…for rhetorical gain.” (Tilley, 2013) Regarding Batman, Wertham wrote about a young client who related his homosexuality to that of Batman and Robin. In one instance he cites the following:

“One young homosexual during psychotherapy brought us a copy of Detective Comics, with a Batman story. He pointed out a picture of ‘The Home of Bruce and Dick,’ a house beautifully landscaped, warmly lighted and showing the devoted pair side by side, looking out a picture window. When he was eight this boy had realized from fantasies about comic-book pictures that he was aroused by men. At the age of ten or eleven, ‘I found my liking, my sexual desires, in comic books. I think I put myself in the position of Robin. I did want to have relations with Batman. The only suggestion of homosexuality may be that they seem to be so close to each other. I remember the first time I came across the page mentioning the Secret Bat Cave. The thought of Batman and Robin living together and possibly having sex relations came to my mind. You can almost connect yourself with the people. I was put in the position of the rescued rather than the rescuer. I felt I’d like to be loved by someone like Batman or Superman.’“ (Wertham, 1954)

Tilley’s review of Wertham’s notes reveals that the young client was actually two teenage males who had been in a sexual relationship since childhood. Wertham took their two separate statements, combined them into one, and reworded it to put more weight on the idea that Batman comics encouraged homosexuality rather than simply reminding the older teen of his sexuality, whose statement found in Wertham’s notes reads “The only suggestion of homosexuality may be that they seem so close together, like my friend and I.” Also omitted was the fact that the boys found the characters of Tarzan and Namor the Submariner to be better suited for cultivating gay fantasies than Batman and Robin.

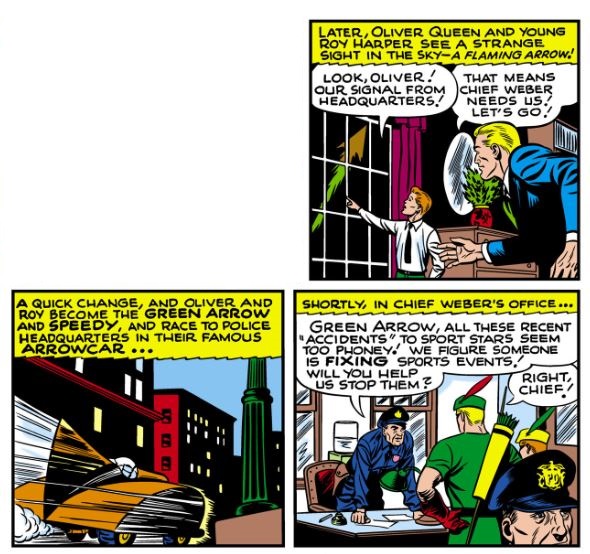

Ultimately Wertham’s fixation on idiosyncratic details like the absence of women in the home or Robin’s lack of pants exemplifies his fishing for an angle that, while proven effective, doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. Superhero stories were primarily written for boys, and elements like the lack of a traditional family home were common in many titles, such as Captain America with the eponymous character and Bucky or World’s Finest Comics with the character Green Arrow and Speedy (a wealthy crimefighter and sidekick replicated to match the Batman and Robin model, complete with “Arrow Signal”, “Arrow Car” and “Arrow Cave” as seen in the panels below). That Wertham never took the larger sample size of the hero-sidekick subgenre and was fixated on Batman suggests both an agenda and a failure of research. The fact that Robin’s costume is patterned after his family circus outfit – and alongside several tights-clad superheroes at the time – also is evaded. Other observations such as Bruce Wayne’s wealth – a fact established well before the character of Dick Grayson was created – and his wearing pajamas around the house imply a grooming objective, but this still belies the function of Robin and how the comics were specifically written. As evidenced by the carefree, neglectful attitude towards women exampled with the characters of Julie Madison and Linda Page, the Batman and Robin stories related to readers the excitement of living a double-life as secret crimefighters. Following the model of heroes like Superman and Zorro, whose alter egos feigned a meek and timid persona to the consternation of their love interests, readers were attracted to protagonists who showed one face to the public and revealed a truer, more exciting face to the audience. (Siegel, 1975) Women didn’t factor into those types of fantasies, or if they did, they were an element of the larger reverie of costumes and criminals, such as the Catwoman.

a few panels from World’s Finest #28

One wonders why Wertham misappropriated the testimonies of his clients to pursue Batman so doggedly. His charges against EC Comics – the violent imagery and horror-themed stories – weren’t nearly as fabricated by comparison. Even his assailing of Wonder Woman as a matriarchal subversive was laden in more truth than fiction, as the original Wonder Woman comics were very much created as propaganda by the radically feminist psychologist William Moulton Marston (Cocca, 2016). It’s also worth noting that Wertham’s intentions were indeed honest when it came to the welfare of children. He was progressive for his time, founding the Lafargue Clinic, one of the first in the country to provide low-cost care to patients of color, off the encouragement of Richard Wright, the author of such works as Native Son. He also gave testimony at the 1951 Desegregation hearings that led to the Supreme Court’s 1954 overturn of Brown v. Board. His critiques against comics regarding depictions of women and minorities appeared genuine, even if they ran up against EC Comics’ effort to combat racial prejudice by means of depicting the consequences of its existence. (Nyberg, 1998)

Whatever his specific reasons, Wertham’s accusations stuck, and the comic book industry was overhauled in a massive way. While superhero comics weren’t severely affected as much as crime and horror books, the Bat-Books would make a concerted effort to combat the charges of endorsing a gay agenda. However, its efficacy in staving off those accusations reveals more than it tried to conceal.

Batman and Robin weren’t in a gay relationship, and they weren’t written to entice young readers, but were they queer? With everything suggested and rejected throughout the Senate Hearings and the Comics Code, what core element of Batman’s sexuality remains fixed, and what remains flexible? More importantly, what remains true?

from Detective Comics #49